Tips for summer success!

Written for the Davis Enterprise, May 09 2013

Feed your plants!

Or feed your soil, and let your soil feed your plants.

I'm running into a frequent problem with organic gardeners

who make their own compost. They're doing everything right: saving leaves and

garden vegetation and composting it, then spreading it around the garden. Then

their plants grow slowly and the older leaves are yellowing: a common sign of

nitrogen deficiency.

You need to fertilize your garden for good growth and

flowering. A standard rate of application that I find in soil service

recommendations and fertilizer handbooks is Ò1000 lbs. of actual nitrogen per

acre.Ó That's a useful statistic if you know how to convert your acreage to

square feet, and how to read a fertilizer label. That's a little more than 2

lbs of actual nitrogen per 100 square feet; 2.3 to be exact, but you don't need

to be exact. 2.3 lbs. of fertilizer? No: actual nitrogen. So you need

to know what percentage of your fertilizer is actual nitrogen.

A little technical overview here.

Every fertilizer you buy, by law, has two things on the

label. The N-P-K formula, and the "guaranteed analysis" telling you

how much of each of those is in the bag, and what the sources are.

N = nitrogen.

P = phosphorus.

K = potassium.

I am not concerned about P or K. Neither is deficient

here.

Here are some examples of guaranteed analyses of

N-P-K:

o 4-6-2

(starter fertilizer, organic)

o 5-10-10 or

5-5-5 (common synthetic tomato-veg foods)

o 6-2-1

(cottonseed meal)

o 13-0-0

(blood meal)

o 16-16-16

(multi-purpose)

o 10-1-4

(natural lawn food)

o 21-0-0

(ammonium sulfate)

That's a lot of numbers. What should you use? How about

manure; is it a fertilizer?

Manure is popular for gardens because it tends to be

inexpensive and readily available. It's a pretty good source of nitrogen, and

provides organic matter that makes the soil looser. Manure ranges from 1 to 3%

nitrogen (steer is lower, chicken is higher). But to provide your nitrogen

completely with manure, you'd need (for that 100 square foot bed) 75 lbs. of

chicken manure (about four bags) or 230 lbs. of steer manure (six to ten bags).

You can provide ten to twenty percent of your nitrogen needs

by growing a cover crop in the fall and winter. Legumes, which are plants in

the bean family, 'fix' nitrogen from the atmosphere in the root zone, helping

to feed other plants. A solid bed of fava beans, vetch, or clover can reduce

the amount of plant food you need to apply. But they won't provide it all.

Your own home-made compost doesn't have much nitrogen. It's

a great thing to add to your soil, but not for its plant food value.

Here's what I do.

o I

incorporate some all-purpose garden compost to the whole garden bed each

year, spreading an inch layer on top and turning it in. What I use contains 15%

chicken

manure. If you're using your own compost, add some extra manure.

That's four bags (2 cubic foot) per 100 square feet.

o I add a

small handful of an organic

fertilizer that's 10% nitrogen in each planting hole as I put the

seedling in. That's about 10 lbs. of fertilizer per 100 sq. ft.

o I grow

cover

crops, mostly fava beans or vetch, in garden beds in the winter,

and I just mow those off in spring and spread the leafy top matter around. That

provides about 10% of my total nitrogen, and the tops and roots enrich the soil

as they decompose.

By my estimates, that all adds up to about 2 lbs. of actual

nitrogen. I sometimes feed high-yielding plants like peppers and eggplant again

during the summer, simply by sprinkling some more fertilizer alongside them and

watering it in. And I plant bush beans in as many little corners as I can,

because they put nitrogen in the soil as they grow.

Already planted your vegetables or flowers? That's fine.

Just spread some fertilizer around them and carefully cultivate it into the top

inch of the soil, then water it in.

Organic or synthetic?

Organic fertilizers are lower-nitrogen, so you need more

pounds of them. They are somewhat more expensive than synthetic fertilizers.

But there's a big difference: they release their plant food more slowly and

steadily through the season. And the plant food is in the form of organic

matter that breaks down and improves the soil structure.

With organic fertilizers, the nitrogen availability is a

function of soil temperature, so they tend to be there for the plant when the

roots are growing and the plant needs it. Organic fertilizers only need to be

applied once a season. And you're very unlikely to mis-apply them and burn the

plant.

Common sources of organic nitrogen, often blended in mixes,

include:

o Alfalfa meal

(very low nitrogen)

o Bat or

seabird guano

o Blood

meal

o Cottonseed

meal

o Feather

meal

o Fish

emulsion or meal (great to get seedlings going)

Synthetic fertilizers are higher-nitrogen and cheaper. They

are derived from petroleum products. You can feed a garden bed for a few

dollars, and you see faster results. But they release all of their nitrogen

very quickly, promoting vigorous and sometimes tender new growth. They're

salts, which can damage roots if applied at rates higher than the label

recommendation, and can damage those beneficial soil organisms that help plants

feed themselves. They can burn the plant if they aren't watered in immediately

and thoroughly. Within a few weeks they're gone, so you may need to fertilize

again a couple of times during the season.

Common sources of synthetic nitrogen include:

o Ammonium

phosphate

o Ammonium

sulfate

o Potassium

nitrate.

o Urea

Water carefully.

"Check daily, water as needed."

Newly transplanted vegetable and flower seedlings may need

water every other day for the first few days. Within a week or so their roots

have made a surprising amount of growth, at which point you can water longer

and less often. Water thoroughly, deeply, and as infrequently as possible. We

see a lot of young plants watered more often than needed.

Be aware of special situations.

Raised planter beds, and loose sandy soils drain faster and

need more frequent irrigation. They don't hold nutrients as well, so you may

need to apply nitrogen a couple of times during the season. In most other

situations, one application would be fine.

Cage your tomatoes well.

The time to plan for the rambunctious growth of your tomato

plants is when you plant them. Once they get going they become increasingly

difficult to corral into reasonable production units. Most tomatoes are what we

call indeterminate, meaning it is a vine that keeps growing all summer and into

the fall, often to ten feet or more. Those cute little tomato cages sold at

most garden stores are no match for a normal tomato in the Sacramento Valley!

Make your own cages out of concrete wire that you buy from the lumber store.

They need to be at least six feet tall, and staked securely.

Don't freak out about the weather.

When we get our first day in the 90-degree range, people

start to ask Òisn't it getting kind of late to plant?Ó No! Soil temperatures

for summer vegetables and warm-season flowers are just getting where we want

them! I plant peppers and eggplant in May or June, and continue planting beans

into July. Some of our favorite flowers love heat and loath cold: verbena,

lantana, zinnias are some of the easy stars of the summer garden. Shrubs and

trees go in just fine during warm weather so long as you water them properly.

Summer is the very best time to plant citrus trees; plants root and grow very

quickly in warm soil.

Manage your summer pests wisely.

Wash off your plants regularly with a strong blast of water.

This kills aphids, mites, and other insects and removes dust from the leaves. A

regular vigorous shower, preferably early in the day, can prevent a lot of pest

problems.

Know the good guys! Beneficial insects are hard at work in

your garden. Summer gardens rarely need any pesticides.

Smother summer weeds. Weeds that sprout in May grow very

fast and take over by August. Good quality landscape fabric can minimize weed

problems and help conserve soil moisture.

Plant some flowers among your edibles.

Or some edibles among your flowers. Certain flowers draw

beneficial insects into your garden. Cosmos and marigolds draw butterflies,

borage draws bees, sweet alyssum attracts beneficial predatory insects.

Diversity is always good in the garden.

For picture links, visit the original article at http://redwoodbarn.com/DE_summersuccess.html

For picture links, visit the original article at http://redwoodbarn.com/DE_summersuccess.html

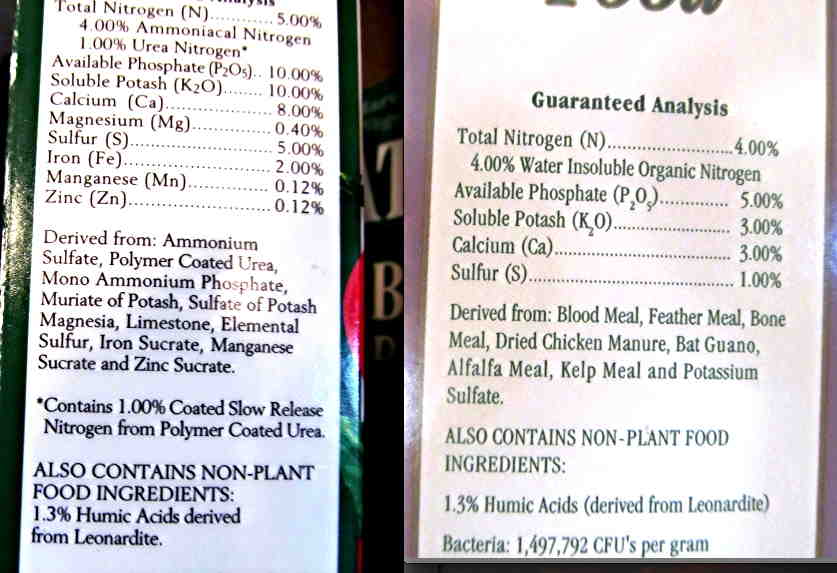

The label on the fertilizer bag or box tells you what's in it and what it's made from. On the left is a typical synthetic fertilizer. Most of the nitrogen sources are petroleum products. The nitrogen in the organic fertilizer on the right is mostly from animal byproducts.

Get your cage on your tomato plants while they're still small! This simple cage system is shown about four weeks after planting. It's made from concrete wire available from your local hardware or lumber store. Ask for the six inch grid, so you can get your hand through to pick the tomatoes! Just poke branches back in when they try to escape. Note the landscape fabric to reduce summer weeds. Good quality fabric can last for several years.

© 2013 Don Shor, Redwood Barn Nursery, Inc., 1607

Fifth Street, Davis, Ca 95616

Feel free to copy

and distribute this article with attribution to this author.

Click here for

Don's other Davis Enterprise articles

One thing that I plan to do more of in the future is to check the UC Davis website for "bee and butterfly" friendly flowering annuals, obtain seeds from those selections, and grow them out at home before transplanting to the summer garden. I have found that many types of bees are attracted to flowers that honeybees pass right over. The battleship sized Carpenter Bee for example, can't get enough of open tomato flowers. When I see those big bees drilling into those flowers, it means a tomato will form there eventually.

ReplyDelete